Roberto Bolaño

”

“

So what’s quality writing? Well, what it’s always been: knowing how to put your head in the dark, knowing how to jump into the void, knowing that literature is fundamentally a dangerous trade.

— Roberto Bolaño,

Between Parentheses

The work of the late Roberto Bolaño has grown even more urgent in the years since his death. At the heart of his novels is the idea that the concentration camp never went away for good — that the horrors of the early twentieth century are coming back at strange new latitudes.

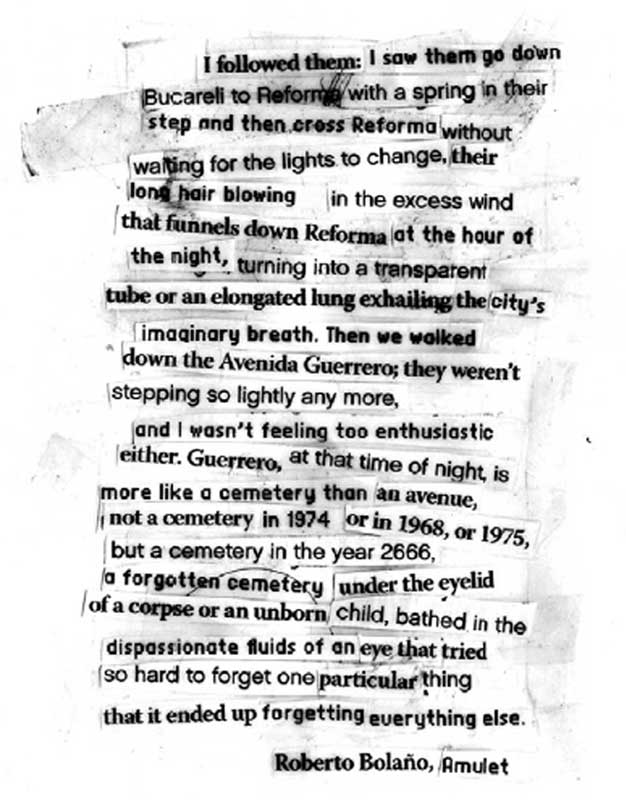

Having left his native Chile in his late teens, Bolaño spent the better part of his youth drifting around Central America andMexico before eventually ending up in Spain, where he took up writing novels as an alternative to washing dishes. His longest and most acclaimed book, the posthumous 2666, is a study of the last hundred or so years of mass death, stretching all the way from the corpse-strewn waste-dumps of present-day industrialMexico to the abandoned shtetls of Nazi-occupied Ukraine.

His other masterwork, The Savage Detectives, follows a generation of Latin American artists sent into exile by a wave of state terror that enveloped the continent virtually until the millenium. Latter-day and more desperate beatniks, his characters sketch the potential for art in a world where the death squad, the prison camp and the mass grave have become the rule and not the exception of politics as such.

”

“

For the bourgeoisie and the petite-bourgeoisie, life isa party. They have one every weekend.The proletariat doesn’t have parties.Just funerals with rhythm.

That’s going to change. The exploited are going to throw a big party. Memory and guillotines. Intuiting it, acting it out on certain nights, inventing edges and humid corners for it, like caressing the acid eyes of the new spirit.

— Roberto Bolaño,

Infrarealist Manifesto

The definitive moment in Bolaño’s own political and artistic education was undoubtedly the coup d’état in Chile. Living in Mexico when SalvadorAllende came to power, Bolaño quickly made plans to return to Chile in order to support the newly elected government in building socialism.Hitchhiking most of the way from Mexico City toSantiago, Bolaño arrived in the city just a few days before the military junta stormed the presidential palace and forced Allende to commit suicide.

Suspected of left-wing sympathies, Bolaño was pulled off a public bus by government forces and put in jail. He spent his eight-day stint in prison writing poetry, begging food off of his cell mates (the guards hadn’t given him any) and trying to sleepover the sound of other inmates being tortured. Expecting to be transferred to a prison camp or tortured himself, Bolaño was eventually released thanks to two guards that knew him from secondary school. He left the country shortly after, making the trip north stone-broke and with his dream of a socialist Chile destroyed.

Returning to Mexico City, Bolaño was determined to make a name for himself as a writer. Borrowing a phrase from painter Roberto Matta, Bolaño inaugurated his own artistic program: “blow the brains out of the cultural establishment.” Revolting against the stodgy and often apolitical nature of the Latin American literary scene, Bolaño became the ringleader of a group of avant-garde poets and wastrels dedicated to harassing the grandees of Mexican letters. Known for his acerbic poetic output, Bolaño was equally famous for interrupting the events of writers he considered sell-outs or talentless—at one point even sabotaging a reading given by Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz.

The life of Roberto Bolaño is a testament to how much someone with a bomb-thrower’s spirit can accomplish without ever racking up a body count. Artistically innovative and politically uncompromising, his work is an invitation to action in the face of disaster, to not stand mute among the rubble, but to instead fend off the calamities on the horizon.

”

“

When people read his books they have an uncontrollable desire to hang the author in the town square. I can’t think of a higher honor for a writer.

— Roberto Bolaño,

Between Parentheses